Amal and Gordon meet on the opulent streets and shadowy alleys of Taksim, the commercial heart of Istanbul where every conceivable transaction takes place. She is a Syrian refugee, he a privileged westerner from northern Europe. What follows is a dream-like dance, an impossible meeting where these two acknowledge and ignore the barriers between them. The anonymity of the metropolis and their own transience allows them to reinvent themselves, though in reality, they can’t escape who they are or what they represent. Individual stories, images and impressions gathered by Zajac through visits to Istanbul and interviews with Syrian women rebuilding their lives in the city give voice to the characters, particularly to the voice of women, in relation to gender politics and resistance to war and exploitation. THE SKY IS SAFE is a love story, a war story and a microcosm of our time.

|

Names and places have been changed to protect the anonymity of the women whose stories are told in this play.

Very special thanks to Amal, Marwa, Wafa, Farida, Rania, Mona and Sawsan for their generosity and bravery in meeting and telling their stories, and to our translator in Istanbul, Bashar Akak. These meetings took place through the refugee support charity Small Projects Istanbul (SPI). We also owe a debt of gratitude to SPI staff, including Shannon Kay and Lauren Simcic. DROP EARRINGS NOT BOMBS ! PLEASE SUPPORT SMALL PROJECTS ISTANBUL Small Projects Istanbul is a grassroots NGO in Istanbul working with families displaced by conflict in Syria and the MENA region to rebuild their lives through livelihood and community integration initiatives. Their 40+ weekly programs are run by a team of international volunteers and focus on children's educational support, business skills for women of their Olive Tree Craft Collective, and community building. They rely on independent donors for continued programming and all contributions are used to make maximum impact for the growing community they work with. Learn more about Small Projects Istanbul by visiting: www.smallprojectsistanbul.org/liftup2017 Support the makers of the craft collective by purchasing their unique handicrafts: www.dropearringsnotbombs.org |

Writer’s Note – Matthew Zajac

In autumn 2012, I left Edinburgh on a flight to Istanbul. I was due to spend two days there in order to pick up a visa for my onward journey to Iran to play a role in a new Iranian feature film, an intriguing and exciting opportunity. The previous year, the British Embassy in Tehran had been ransacked by a mob. The British diplomatic mission withdrew and, in turn, Iran’s diplomats were expelled from the UK. With no Iranian Embassy in London, my Iranian employers had arranged for the visa process to go through their Istanbul Embassy. The day after I arrived, I received a call from my contact in Tehran to say there had been a delay in the processing of my visa and that I would have to stay for a few more days. This eventually stretched to nine. When I finally visited the Iranian Embassy to pick up the visa, I was asked for an authorisation number, which I had not received. A couple of hours later, I was called once more by my contact. She informed me that the visa had been refused because of my nationality. My job on the film evaporated, my dream of stardom in Iranian cinema remaining just that. I returned to Scotland almost empty-handed. But I had the seed of an idea for a new play for Dogstar.

Of course, Istanbul is an incredibly fascinating city, enormous and vibrant, the meeting place of Europe and Asia. Since my first visit to the city, 25 years earlier, it had undergone great changes, with a frenzy of development taking place: major infrastructure projects such as a brand new subway system; new bridges across the Golden Horn and the Bosphorous; and thousands upon thousands of new homes, schools, hospitals, cultural centres, mosques and industrial premises.

And during my explorations of the streets around Taksim square, I had come across several interesting characters. One particular encounter, with what I can only describe as a street hustler, gave me the germ for this project, well, more than a germ as I went on a rather interesting and discomforting little trip with him in the bustling commercial district centred around Taksim Square….

Since that stay in 2012, the Syrian tragedy has unfolded, with all its horrors and profoundly unsettling results. Istanbul has been and remains a nexus of world politics, a mighty conduit for the traffic of ideas, ideologies, trade, religions and people, flowing in all directions. The city is now home to over 350,000 Syrian refugees, many of whom are destitute, or close to it, working and struggling to rebuild their lives, feed their families and keep a roof over their heads.

Turkey’s straddling of Europe and Asia, and the multifarious tensions this produces, provides a virtually unlimited source of stories and dramas. I had my own, very limited and individual experience and I wanted to use it to start generating a small drama about two individuals in this vast metropolis with all it and they represent. It was impossible for me to ignore the impact of the Syrian war on Istanbul, the Middle East and Europe, so I decided to try to explore the experience of Syrian refugees in the city and the relationship we in the West have with them and with the disintegration of their country. In particular, I wanted to focus on the experience of women because it seemed crucial to me that this play wasn’t only about the impact of war on individuals and the relationship of the West to the Middle East, it also had to be about the politics of gender.

I was very lucky to discover and enlist the help of Small Projects Istanbul, a grass-roots NGO operating in Istanbul to help those displaced by the conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa. SPI runs a community education centre in a densely populated neighbourhood of the city. Families and individuals participate in a number of initiatives including language classes, a women’s craft collective and music, art and computer classes. A crucial benefit of SPI’s work is to create an environment where people who have undergone the most extreme trauma can find support and friendship. This has a direct impact in improving psychological well-being.

Through SPI, I experienced the great privilege of meeting the women who provided me with the words and stories which form the major part of The Sky Is Safe. These women are a testament to the strength of the human spirit in the greatest adversity. Their dignity and their determination to build new lives for themselves and their children is at once inspiring, heartbreaking and infuriating. The historical failure to create equity in the Middle East has opened the door to nihilism and horrific conflagration. Death feasts on the region through another war constructed by men. When will we learn from the folly of war ?

In Edinburgh at the beginning of this year, I was introduced to the Syrian Kurdish artist Nihad Al Turk and his wife Sawsan Osso by my friend, the painter James Lumsden. Sawsan, Nihad, and their two young daughters, are among the small number of Syrians who have been allowed to settle in Scotland. I was immediately struck by the strength and sensitivity of Nihad’s work and knew that I had been presented with a great opportunity to reinforce the creative power and authenticity of our play by asking him to design the set. We are lucky to have Nihad, Sawsan and their friends Laurance Darwish and Fatima Tahir contributing to this production and to Scotland.

It is to the women, Marwa, Rania, Wafa, Sawsan, Mona, Farida and Amal, and to our translator Bashar, that I dedicate this work.

In autumn 2012, I left Edinburgh on a flight to Istanbul. I was due to spend two days there in order to pick up a visa for my onward journey to Iran to play a role in a new Iranian feature film, an intriguing and exciting opportunity. The previous year, the British Embassy in Tehran had been ransacked by a mob. The British diplomatic mission withdrew and, in turn, Iran’s diplomats were expelled from the UK. With no Iranian Embassy in London, my Iranian employers had arranged for the visa process to go through their Istanbul Embassy. The day after I arrived, I received a call from my contact in Tehran to say there had been a delay in the processing of my visa and that I would have to stay for a few more days. This eventually stretched to nine. When I finally visited the Iranian Embassy to pick up the visa, I was asked for an authorisation number, which I had not received. A couple of hours later, I was called once more by my contact. She informed me that the visa had been refused because of my nationality. My job on the film evaporated, my dream of stardom in Iranian cinema remaining just that. I returned to Scotland almost empty-handed. But I had the seed of an idea for a new play for Dogstar.

Of course, Istanbul is an incredibly fascinating city, enormous and vibrant, the meeting place of Europe and Asia. Since my first visit to the city, 25 years earlier, it had undergone great changes, with a frenzy of development taking place: major infrastructure projects such as a brand new subway system; new bridges across the Golden Horn and the Bosphorous; and thousands upon thousands of new homes, schools, hospitals, cultural centres, mosques and industrial premises.

And during my explorations of the streets around Taksim square, I had come across several interesting characters. One particular encounter, with what I can only describe as a street hustler, gave me the germ for this project, well, more than a germ as I went on a rather interesting and discomforting little trip with him in the bustling commercial district centred around Taksim Square….

Since that stay in 2012, the Syrian tragedy has unfolded, with all its horrors and profoundly unsettling results. Istanbul has been and remains a nexus of world politics, a mighty conduit for the traffic of ideas, ideologies, trade, religions and people, flowing in all directions. The city is now home to over 350,000 Syrian refugees, many of whom are destitute, or close to it, working and struggling to rebuild their lives, feed their families and keep a roof over their heads.

Turkey’s straddling of Europe and Asia, and the multifarious tensions this produces, provides a virtually unlimited source of stories and dramas. I had my own, very limited and individual experience and I wanted to use it to start generating a small drama about two individuals in this vast metropolis with all it and they represent. It was impossible for me to ignore the impact of the Syrian war on Istanbul, the Middle East and Europe, so I decided to try to explore the experience of Syrian refugees in the city and the relationship we in the West have with them and with the disintegration of their country. In particular, I wanted to focus on the experience of women because it seemed crucial to me that this play wasn’t only about the impact of war on individuals and the relationship of the West to the Middle East, it also had to be about the politics of gender.

I was very lucky to discover and enlist the help of Small Projects Istanbul, a grass-roots NGO operating in Istanbul to help those displaced by the conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa. SPI runs a community education centre in a densely populated neighbourhood of the city. Families and individuals participate in a number of initiatives including language classes, a women’s craft collective and music, art and computer classes. A crucial benefit of SPI’s work is to create an environment where people who have undergone the most extreme trauma can find support and friendship. This has a direct impact in improving psychological well-being.

Through SPI, I experienced the great privilege of meeting the women who provided me with the words and stories which form the major part of The Sky Is Safe. These women are a testament to the strength of the human spirit in the greatest adversity. Their dignity and their determination to build new lives for themselves and their children is at once inspiring, heartbreaking and infuriating. The historical failure to create equity in the Middle East has opened the door to nihilism and horrific conflagration. Death feasts on the region through another war constructed by men. When will we learn from the folly of war ?

In Edinburgh at the beginning of this year, I was introduced to the Syrian Kurdish artist Nihad Al Turk and his wife Sawsan Osso by my friend, the painter James Lumsden. Sawsan, Nihad, and their two young daughters, are among the small number of Syrians who have been allowed to settle in Scotland. I was immediately struck by the strength and sensitivity of Nihad’s work and knew that I had been presented with a great opportunity to reinforce the creative power and authenticity of our play by asking him to design the set. We are lucky to have Nihad, Sawsan and their friends Laurance Darwish and Fatima Tahir contributing to this production and to Scotland.

It is to the women, Marwa, Rania, Wafa, Sawsan, Mona, Farida and Amal, and to our translator Bashar, that I dedicate this work.

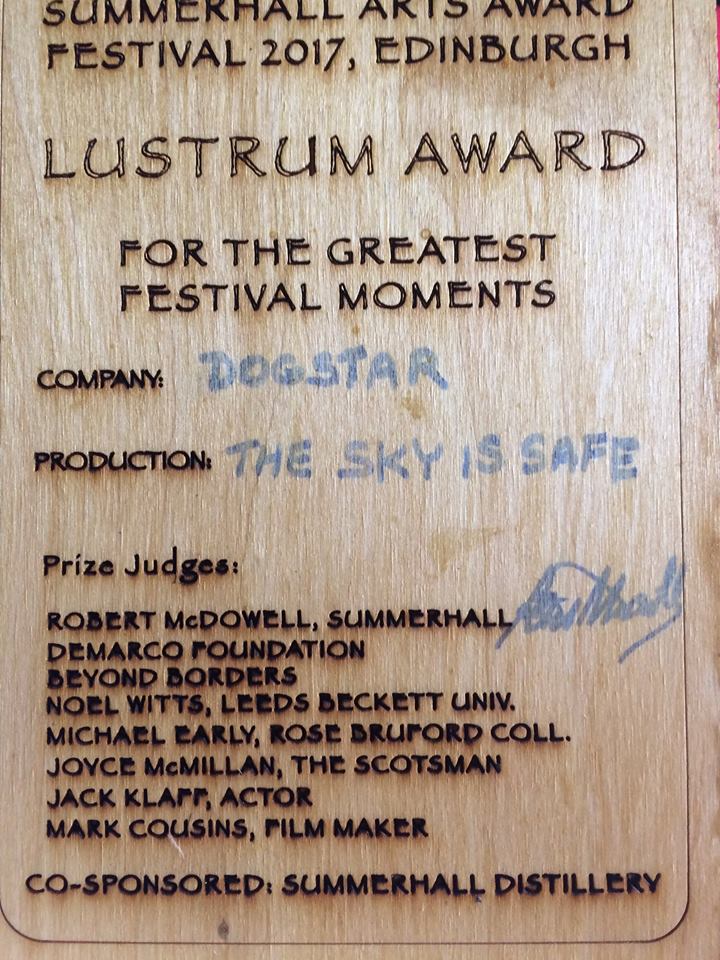

REVIEWS and AWARDS FOR THE SKY IS SAFE

by Matthew Zajac

THE SKY IS SAFE is part of the Scottish Govenment's Made in Scotland programme for the 2017 Edinburgh Fringe

and is also supported by Creative Scotland.

and is also supported by Creative Scotland.